My Enquiry (0)

No artwork has been selected.

Please choose an artwork to enquire.

Enquiry Submitted

Thank you for your enquiry and interest in our artists’ work. A member of the gallery team will respond shortly.

000%

16 May - 30 August 2025

In Us is Heaven brings together 17 multidisciplinary artists whose practices platform Queer identity in beautiful, heterogeneous ways and across various positionalities and experiences, globally.

In Us is Heaven serves as both sanctuary and site of confrontation. Negotiating heterogenous experiences and aesthetics, the exhibition’s works contend that Queer art is not marginal or other – it is everywhere, existing and persisting in the intersections of our cultural, political, spiritual and emotional landscapes. The exhibition questions systems of regulation that enforce difference, shame and social failure, advocating for healing through the infinite resource of unbounded love.

Featured artists include Queezy Babaz, Jody Brand, Chloe Chiasson, Lea Colombo, Simon Haas, Alex Hedison, Rich Mnisi, Zanele Muholi, Ambrose Rhapsody Murray, Oluseye, Catherine Opie, Araba Opoku, Jody Paulsen, Athi-Patra Ruga, Brett Charles Seiler, Chiffon Thomas and Qualeasha Wood.

The exhibition embraces Cuban-American scholar José Esteban Muñoz’s proposition that “Queer utopia” exists in the now as a possible but not-yet-reached horizon. In Us is Heaven explores the fluid contours of Queer being not only as lived experience but as a visionary realm where personhood and autonomy are reimagined beyond the binary confines of heteropatriarchy, normative function, nationalism, and coloniality.

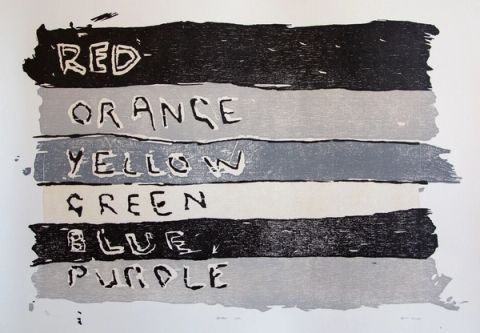

Brett Charles Seiler’s Rainbow Flag mural, painted on the gallery’s external street-facing wall, reflects the collective sentiment of the Queer community this Pride Month. Drained of its usual vibrancy – the gay pride colours signified only through text – Seiler’s desaturated iteration speaks to the loss, grief and uncertainty faced by the LGBTQIA+ community.

The predominant presence of photography, as both documentary and speculative form, serves here as a mode of reclamation. The early 20th century saw the medium weaponised against the Queer community through surveillance, police records, and psychiatric documentation. In response, artists and activists sought to image themselves in love, protest, joy and camaraderie, offering personal counter-narratives to mainstream erasure and the proliferation of reductive images of Queer life.

Catherine Opie’s Portraits series (1993–1997) destabilizes the nostalgic trope of the all-American family portrait, presenting members of Los Angeles and San Francisco’s lesbian, gay, Trans, and sadomasochistic communities in studio settings. Opie’s photographs reject the portrait format’s associations with heterosexuality, capitalist values and traditional gender roles, manifesting an intimate vision of partnerships built on chosen kinship, survival and unflinching erotic solidarity. Though the practices of Opie and Zanele Muholi are location specific, they are not location bound. Both artists have cultivated aesthetic environments for collective belonging and counter-hegemonic representation, developing transnational archives for multiplicitous self-identification.

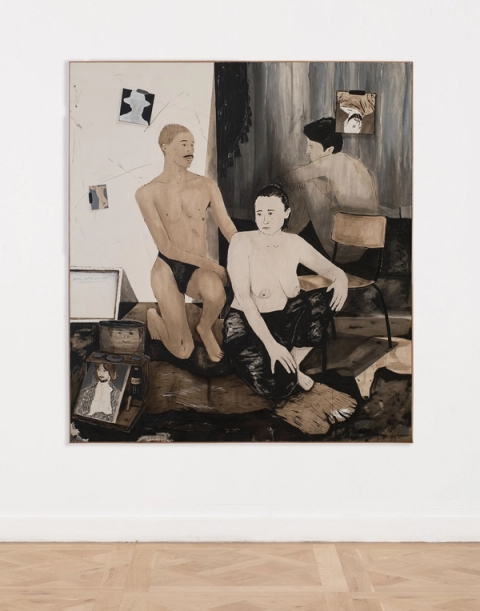

The devotional portrait is further reimagined in Brett Charles Seiler’s large-scale painting, Shakil and Laura (To Rub Hurt Feelings), a cinematic window into the community of friends, chosen family, lovers and former lovers that animate his world. The intimate corners of the artist’s life unfold in this studio scene in which a man and a woman – friends of one another and of Seiler – pose for their portrait, surrounded by paintings, erotic studies, preparatory sketches and photographs of other friend-models. The soft resistance of everyday bonds – casual, deep, physical, platonic – are the subject here as Seiler’s practice pivots around grace, vulnerability, peoplehood, and love. Simon Haas’ graphite drawing distills a personal moment of this same togetherness. Haas’ rendering captures his husband and two beloved friends swimming against the shifting tides off New York’s Fire Island – a storied stretch of coastline long cherished as a haven for the local gay community.

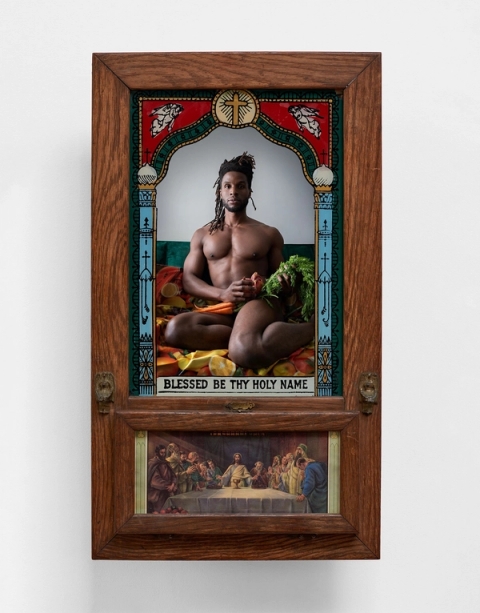

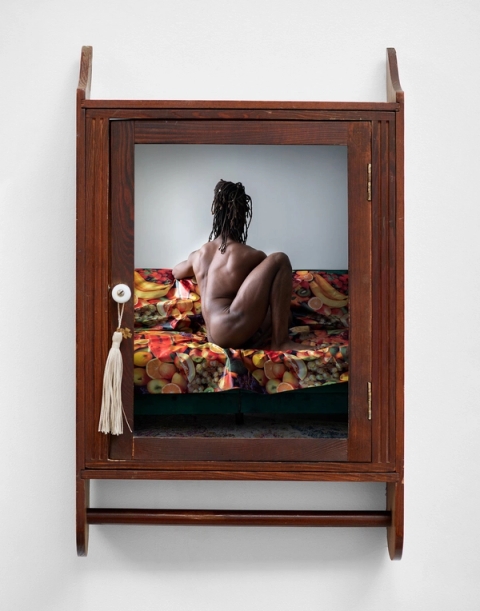

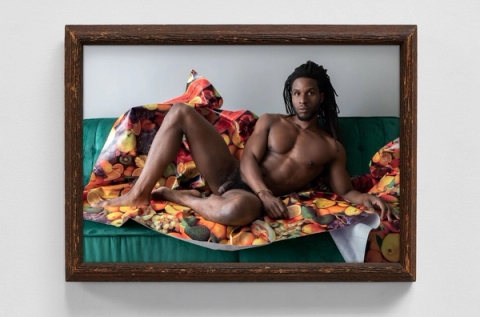

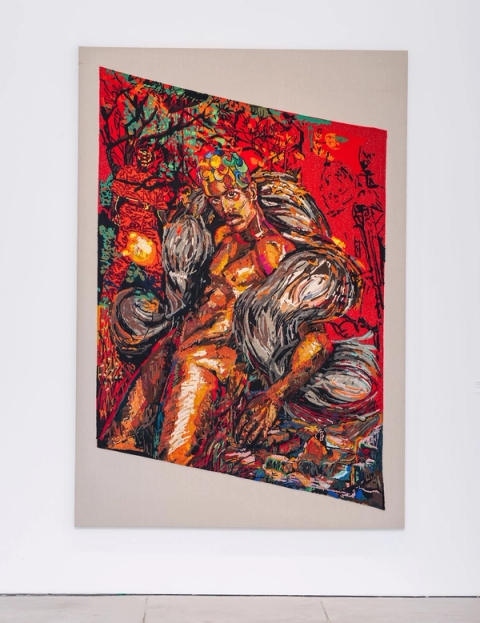

A growing body of decolonial and African feminist scholarship interrogates the imposition and legacy of Western gender binaries on African societies, revealing these as central – rather than peripheral – consequences of colonial rule and Christian missionary activity. Works by Oluseye and Athi-Patra Ruga speak back to doctrine by restaging the ornate artifice of biblical narrative. Oluseye’s Steve photographic series – whose title is an arched reference to the homophobic adage “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” – depicts the artist enacting a ritual of unlearning and reconstitution. Individually titled The Fall of Man (Sin), Act of Contrition (Shame), The Revelation (Self-acceptance), the self-portraits confront colonial Christianity’s violent history while reclaiming Queer embodiment as divine. Ruga’s hallucinatory tapestry, Jacob About to Wrestle an Angel, sees the artist render himself in the image of Senegalese Cabaret dancer Féral Benga. Striking a pose of come-hither provocation, Ruga’s figure is without male or female genitalia. This withholding interrogates the racialised and gendered economies of desire, calling keen attention to the phallus as a site of both fixation and critique. Drawing on African traditions, camp aesthetics and the expansive history of fetish culture, Ruga’s works offer us a flamboyant glimpse into the artist’s self-devised pantheon of Queer saints and mythological avatars.

Gender as social performance – in all its learnt custom and codified gesture – occupies a central thematic throughline. Both Muholi and Queezy Babaz celebrate Queer pageantry, drawing from their own personal histories. Muholi’s Miss Lesbian I, Amsterdam is a nod to Ms Sappho, a pageant for Black Queer women held in South Africa in the late ’90s in which the artist themself participated 28 years ago. The portrait has retained its radical value, emblematic of Muholi’s world-building impulse to image and illuminate alternative lesbian and non-binary corporality. Queezy’s kaleidoscopic digital print interweaves family photographs with archival images from Miss Gay Western Cape, an ongoing Cape Town-based pageant first held in 1996. The artist regards the work as an extension of drag performance – a ritualised spectacle of performing the self – referencing different aspects of their identity and heritage: indigenous (Khoi and San) cosmologies, Queer rites of passage, contrasting cultural styles and belief systems.

Gender as performance requires the symbiotic gaze of another, made real through the awareness of being perceived. The exaltation of the human form is explored in the work of Rich Mnisi, Lea Colombo, Jody Paulsen and Jody Brand. The hyper-masculine bodybuilder in Mnisi’s Matimba (Strength), speaks to cultures of body conditioning within gay communities, where the body becomes either a signifying trophy or a territory for scrutiny. Beyond this internalised consciousness of being seen, Mnisi conjures the vulnerability and plurality of all masculinities, gestured in the closed eyes of his otherwise hardened subject. Paulsen also toys with notions of excess in a sumptuous felt collage that reimagines Titian’s Venus of Urbino as a “regular girl” surrounded by the accoutrements of privileged womanhood. The material opulence, the almost palpable self-indulgence, embody a campified femininity that Paulsen implies is both aspirational and repellent.

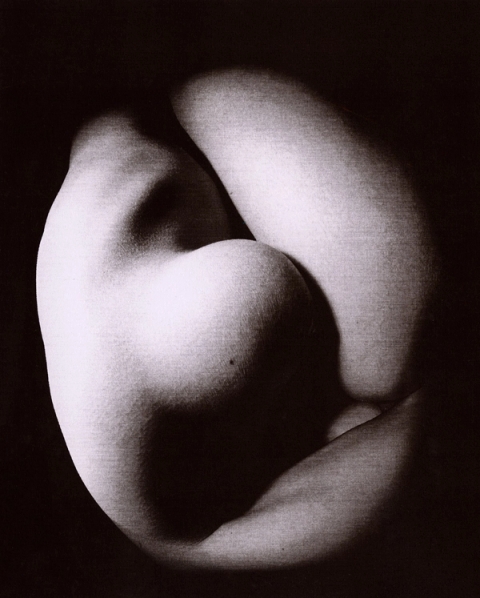

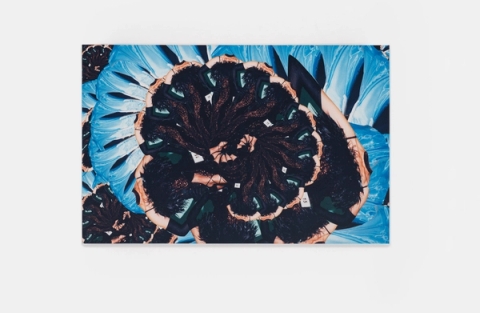

In Colombo’s photographic self-portraits, the body is arranged in artful compositions framed by elements including sacred geometry, colour and reflected light. Approaching the female figure as a study in abstract form, her intervention invites us to consider its metaphysical aspects and the interrelation between matter and spiritual energy.

Brand builds a photographic altar to Black, Queer resilience in a portrait series that reconfigures the visual cues of domination. Envisioning the multiverse of experiences and complex personhood of her collaborators (including fellow artist Queezy Babaz), she disrupts homogenous tropes of victimhood and trauma around the lives of femme individuals who exist outside of the centres of power. The series pays tribute to Nokuphila Khumalo, a 23-year-old South-African sex worker, murdered in 2013 by a well-known South African artist-photographer.

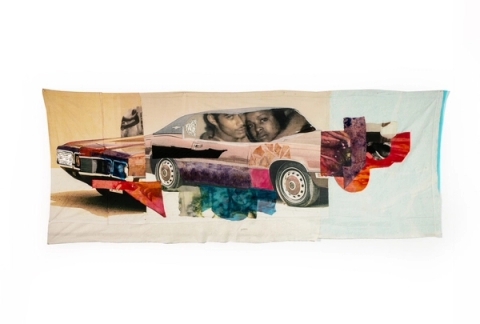

The works of Ambrose Rhapsody Murray and Chloe Chiasson disrupt the symbol of another trophy of American machismo. In the retro-terrain of the American South, the car is a vehicle for boyhood memory, familial mythologies and aspirational commodity. While Murray’s fractured rendering of the car collapses and blends generational memory with their own sense of longing and reinvention, Chiasson’s sculptural imagining of the trunk of a pickup truck – strewn with emblems of Southern masculinity like Shiner beer and Marlboro Reds – becomes a podium for a lesbian embrace. The oversized scale of both works declare a desire to occupy space, to disintegrate the tension between our private worlds and the surveilled public domain.

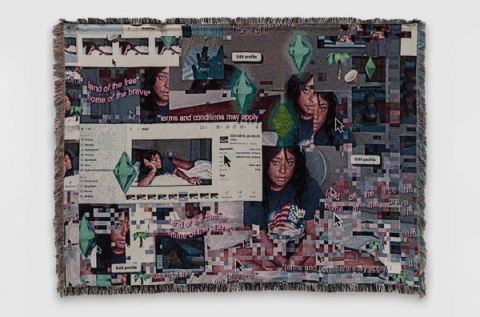

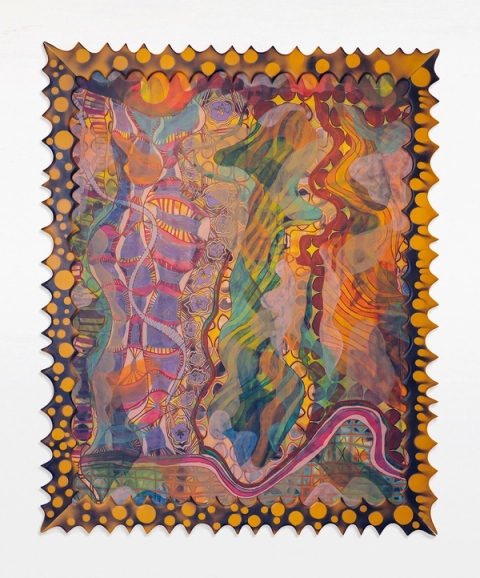

As public spaces regress into systematically policed spheres for gender non-conforming persons, Qualeasha Wood and Araba Opoku nurture speculative, abstract realms for creation and identity formation. Wood interlaces tapestry with avatar and code, citing the virtual world and internet culture as a familiar, adolescent plane for digital play and autonomous self-imaging. i believe there’s meaning / i believe there’s nothing depicts the artist clad in a t-shirt bearing the American flag and crowned by a Sims diamond, her avatar standing as both shield and surrogate in navigating virtual possibility and the real-world precarity of the current political climate. Opoku’s meditative dreamscape, realised through fluid and repetitive mark-making, considers the psyche a portal where healing, failure and transformation coexist. Opoku finds spiritual architecture in intuitive form and pattern, building layered worlds that resist linear temporalities and fixed identity.

José Esteban Muñoz’s vision of Queer futurity is seemingly spied in Alex Hedison’s Untitled #8. Between the thin obfuscation of two silhouetted curtains, a liminal parting reveals a glimpse of technicolour glow. It is toward this visible threshold, this Queered elsewhere, that In Us is Heaven tenderly reaches.

Coinciding with Los Angeles’ Pride Month, the exhibition will be accompanied by a programme of talks and events featuring artists, curators and the broader Queer community.

For press enquiries, please email [email protected]

Artists

Queezy Babaz

Jody Brand

Chloe Chiasson

Lea Colombo

Simon Haas

Alex Hedison

- Rich Mnisi

- Zanele Muholi

Ambrose Rhapsody Murray

- Oluseye

Catherine Opie

Araba Opoku

Jody Paulsen

Athi-Patra Ruga

Brett Charles Seiler

Chiffon Thomas

Qualeasha Wood

Works

Chloe Chiasson

Saving Grace, 2023Oil, acrylic, steel, Plexiglass, aluminum, paper, resin, foam, rosary, air freshener, locket, vinyl, graphite, canvas on panel

98 x 79 x 18 in. | 248.9 x 200.7 x 45.7 cm

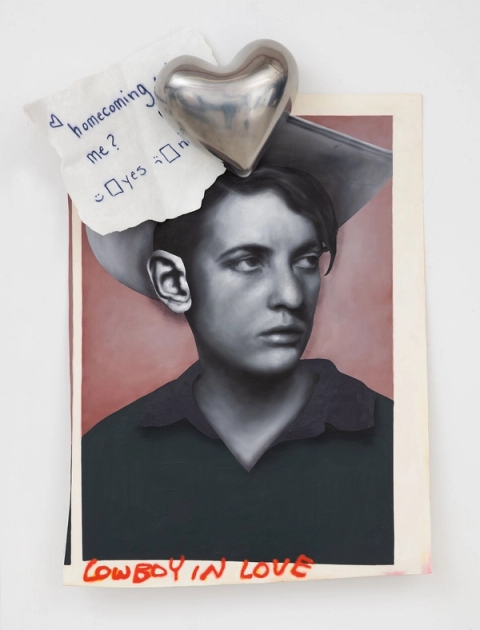

Chloe Chiasson

Cowboy in Love, 2024Oil, acrylic, paper, foam, resin on aluminum

39.5 x 27.8 x 6 in. | 100.3 x 70.5 x 15.2 cm

Sold

Catherine Opie

Daddy Irwin and Mark, 1994Chromogenic print

Image size: 40 x 30 in. | 101.6 x 76.2 cm

Edition 6 of 8, 2 AP

Catherine Opie

John and Scott, 1993Chromogenic print

Image size: 20 x 16 in. | 50.8 x 40.6 cm; Framed size: 21.3 x 17 in. | 54 x 43.2 cm

Edition 2 of 8, 2 AP

Catherine Opie

Mike and Sky 2, 1994Chromogenic print

Image size: 20 x 16 in. | 50.8 x 40.6 cm; Framed size: 21 x 17 in. | 53.3 x 43.2 cm

Edition 8 of 8, 2 AP

Lea Colombo

Rotation of Self, 2021Giclee print on Fuji gloss paper

Image size: 31.4 x 39.1 in. | 80 x 99.5 cm; Framed size: 40 x 32.2 in. | 101.5 x 82 cm

Edition 1 of 3

Lea Colombo

Seeing Beyond, Pyramid of Self, 2024Giclee print on Fuji gloss paper, birch frame, mirror

37.4 x 47.6 x 4.3 in. | 95 x 121 x 11 cm

Oluseye

The value of my dreams will not drown me , 2023Bronze

3.5 x 4.75 x 6.75 in. | 6.5 x 10 x 15 cm

Edition 27 of 48

Oluseye

The value of my dreams will not drown me , 2023Bronze

3.5 x 5.5 x 8.13 in. | 6.5 x 10 x 15 cm

Edition 31 of 48

Oluseye

Steve, Act I: The Fall of Man, 2019Baryta print, Catholic last rites box

23 x 13 in. | 58.4 x 33 cm

Variable edition 1 of 3, 2AP

Oluseye

Steve, Act II: Act of Contrition, 2019Baryta print, vanity box

21 x 13 in. | 53.3 x 33 cm

Variable edition 1 of 3, 2AP

Oluseye

Steve, Act III: Revelations, 2019Baryta print, found frame

25.4 x 35.6 in. | 25.4 x 35.6 cm

Variable edition 1 of 3, 2AP

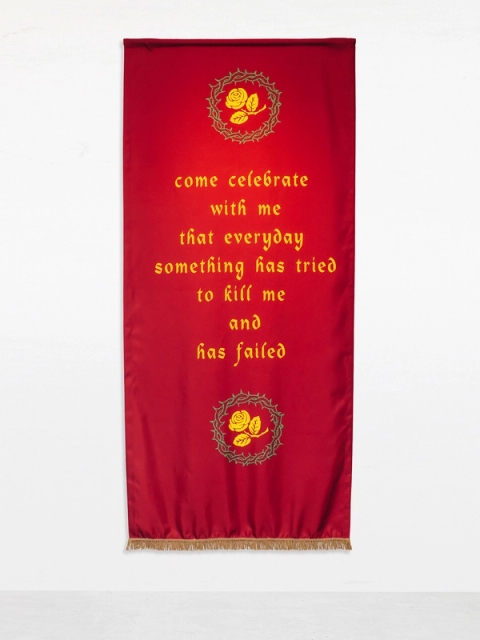

Ambrose Rhapsody Murray

‘Cross roads, 2024Sublimation prints, acrylic on dyed silk and muslin

45.5 x 118 in. | 115.5 x 299.7 cm

Athi-Patra Ruga

Swazi Youth After, 2019Stained glass, lead, powder-coated steel

73.2 x 39.2 x 1.6 in. | 186 x 99.5 x 4 cm

Edition 2 of 2, 1AP

Athi-Patra Ruga

Jacob About to Wrestle an Angel, 2021Wool and thread on tapestry, on canvas

94.5 x 65.2 in. | 240 x 165.5 cm

Zanele Muholi

Mahone, Durban, 2021Baryta print

Image and paper size: 23.6 x 23.6 in. | 60 x 60 cm

Edition of 8, 2 AP

Zanele Muholi

Miss Lesbian I, Amsterdam, 2009Baryta print

Image size: 30 x 19.9 in. | 76.5 x 50.5 cm -- Paper size: 34 x 23.8 in. | 86.5 x 60.5cm

Edition of 8, 2AP

Zanele Muholi

LiZa I, 2009Baryta print

Image size: 30.1 x 19.9 in. | 76.5 x 50.5 cm -- Paper size: 34 x 23.8 in. | 86.5 x 60.5 cm

Edition of 8, 2AP

Brett Charles Seiler

Shakil and Laura (Help to Rub Hurt Feelings), 2025Bitumen, roof paint on canvas

202 x 181.5 cm | 79.5 x 71.5 in.

Brett Charles Seiler

Rainbow Flag, 2024Woodcut on Tiepolo cotton rag paper

25.6 x 19.7 in. | 65 x 50 cm

Edition of 25

Qualeasha Wood

i believe there’s meaning / i believe there’s nothing, 2024Woven jacquard, glass seed beads, hand embroidery

53 x 74 in. | 134.6 x 188 cm

Alex Hedison

Untitled #8 (Nowhere), 2012Archival pigment print on Hahnemühle photorag

Image size: 41 x 59.8 in. | 101 x 152 cm; Framed size: 40.9 x 60.2 in. | 104 x 153 cm

AP1, Edition of 3, 2AP

Rich Mnisi

Matimba (Strength), 2023Baryta print

Image size: 29.5 x 23.6 in. | 75 x 60 cm; Framed size: 30.1 x 24.2 in. | 76.5 x 61.5 cm

Edition 1 of 7, 2 AP

Rich Mnisi

Rifuwo (Wealth), 2023Bronze, glass beads, stainless steel

29.9 x 86.6 x 33.5 in. | 76 x 220 x 85 cm

Edition of 7

Chiffon Thomas

Untitled, 2024Steel, patinated hydrocal, rebar ties

7.5 x 87 x 24 in. | 61 x 221 x 190.5 cm