My Enquiry (0)

No artwork has been selected.

Please choose an artwork to enquire.

Enquiry Submitted

Thank you for your enquiry and interest in our artists’ work. A member of the gallery team will respond shortly.

000%

22 February - 4 May 2024

Taking a multi-generational and transnational lens, Mother Tongues charts the way in which language and pedagogy is channelled into diverse forms of expression. Though the nature of this enquiry requires a singular focus, its sights must be multiple.

Mother Tongues brings together work by 25 artists from across Africa and the diaspora in a shared exploration of sense-making across time and place.

The term ‘mother tongue’ refers not only to the first language of acquisition, but the first with regard to its importance and the speaker's ability to master its linguistic and communicative aspects. One’s mother tongue is not only how a person positions themselves to the world, but how they position themselves in the world. Like the body, it is a border – a place of contact and confluence, an intersection of negotiations.

The expansion of Southern Guild into California is not unprecedented. In the late 1960s, a group of artists left South Africa in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre, mass bannings and the censorship of political parties and cultural workers, eventually establishing a contact point for the interchange of knowledge and meaning between South Africa and California.

Southern Guilds positions itself at the later trajectory of this artistic migration. Having willed the promises of the future into the now with his cover of The Mamas and Papas hit California Dreaming, it is in Los Angeles where Hugh Masekela, arguably one of the continent's most renowned cultural exports, establishes a home for Afro sounds as an imprint of Motown Records. Where Letta Mbulu lays a vocal track on Michael Jackson’s Liberian Girl. Where the Roots soundtrack is produced with several South African musicians. It is here where another touchpoint emerges: a border – porous and primed for the osmosis of different kinds of “mother tongues” and emergent visual languages.

With this inaugural exhibition, Southern Guild hopes to open a new chapter of exchange. The show occupies multiple contact zones, moving between visible surfaces and interior states. Taking a multi-generational and transnational lens, it charts the way in which language and pedagogy is channelled into diverse forms of expression. Though the nature of this enquiry requires a singular focus, its sights must be multiple.

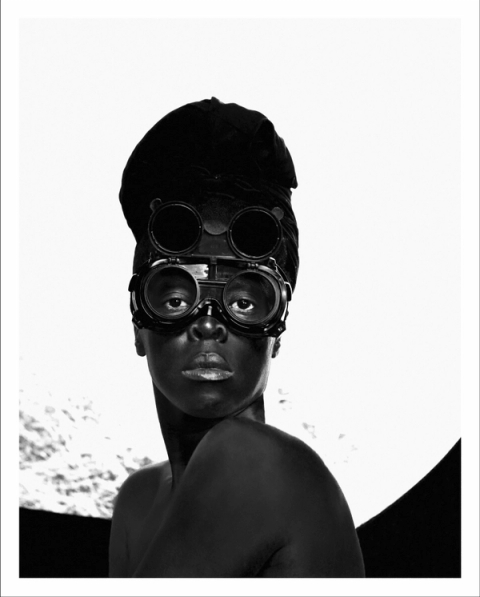

Award-winning visual activist Zanele Muholi’s stark portrait Siyikhokonke speaks to this heterogeneity. They position themselves on either end of the lens, both captured and capturer. Participant and image-maker. Black and white, the work presents itself in contrasts and dichotomy but the title – loosely translated as “we are everything” – speaks to the multiplicity of being. Of everything being everywhere, all at once. Poly, not polar. Where Muholi locates themselves in the frame, the singular standing for many, Jody Paulsen’s portraits are many made one. A corporeal collage, his nude portraiture consists of limbs and ligaments in inked fabric and thread, stitched and spliced together creating a vulnerable, intimate personhood.

Paulsen’s figures present themselves for steady observation, but similar to emerging artist Jozua Gerrard’s masked figures painted in enamel on glass or Justine Mahoney’s collage sculptures, they trouble the act of looking. Here, seeing offers no comfort of context but rather entry points to possibilities of (mis)understanding. This is the lexicon. Fragmented narratives made whole in the mind of the viewer. In Tony Gum’s performative portraits, the body is a continent burdened with stories.

Manyaku Mashilo’s artistic foundation lies in the historically charged realm of portraiture, yet she considers her paintings to be abstractions. Mashilo’s artistic practice serves as a means of sense- making; her canvases function as liminal spaces where she synthesises elements of her religious upbringing, ancestral heritage, a blend of real and imagined myths, folklore, science fiction, music, and sourced archival photographic images. Nigerian-Canadian artist Oluseye also works in the “in-between”, re-animating found objects and detritus collected from his trans-Atlantic travels into talismans akin to those that Africans carried for protection on their forced and voluntary journeys across the ocean. By incorporating Yoruba cultural references, he blends the ancestral with the contemporary, rejecting binary distinctions between tradition and modernity, physical and spiritual realms, past and future, and old and new.

For renowned South African ceramicist Andile Dyalvane, the connection to home comes through his medium – clay or “umhlaba” (mother earth) – a life-force that tethers him to the rural village of his birth. As a medium for storytelling, it is also an essential energetic link to his past, present and future.

Patrick Bongoy’s rubber wall hangings transmute the inert and impermeable material – a harvest heavy with colonial-era exploitation – into tapestries alive with movement and blooming forms. The Congolese artist’s studio operates like a factory in reverse, transforming stockpiles of rubber inner tubes into dense textiles by stripping, cutting, weaving, looping and sewing the material.

Repetitive labour is also the methodology of two other artists working in sculptural assemblage: Dominique Zinkpè, from Benin, whose primary material comprises hundreds of intricately carved Ibéji dolls, and South African Usha Seejarim, who employs everyday objects such as wooden clothes pegs to explore the value of domestic labour and rituals of maintenance and care.

Rich Mnisi’s Nwa-Mulamula’s Chaise, modelled on the shape of his great grandmother’s reclining body, takes its fluidity from organic curves, simultaneously revealing and concealing. Working primarily as a story-teller, Mnisi mines the personal and familial in a manner that turns intimacy into praxis and aesthetic.

Nigerian-British ceramicist Ranti Bam’s terracotta torso vessels abstract and stretch what it means to hold language. Enthralled by etymology, Bam’s creative endeavours are a means of communication. “We express ourselves to encapsulate our experiences in a tangible form, to share,” she reflects.

This intimacy is echoed in Luyanda Zindela’s painstakingly sketched drawings, largely drawn from a series titled Abangani bami – izithombe zami (my friends – my images). Here, the artist posits the idea of close friendships as metaphorical mark-making processes. Drawn to the traditional, laborious nature of cross-hatching, each juncture of line meeting line is an imprint of tenderness, of self.

Chaos/complexity theorists argue that the development and learning of language is not a straight-forward process. Rather, like Africa-centred understandings of time, language is a sloshing, not an ordering. In Kamyar Bineshtarigh’s large-scale paintings, his interest in calligraphy and script makes room for abstraction; lines become blots and language is layered in such a way that its stratifications, if they exist, are imperceptible. Words, histories are things that sit on top of each other.

Languages of the intimate vernacular, or, our mother tongues play an interesting role in how we observe and keep rituals of memory and meaning. Ingrained with its own bureaucracies, rules of engagement honed over time, over place. The personal is political, but the vernacular creates its own politic, veiled in the familial, the traditional, the rituals of the mundane and the magical.

Artists

Ranti Bam

- Kamyar Bineshtarigh

- Adam Birch

- Patrick Bongoy

- Andile Dyalvane

- Jesse Ede

- Madoda Fani

- Jozua Gerrard

Tony Gum

- Porky Hefer

Alexandra Karakashian

- Justine Mahoney

- Chuma Maweni

- Manyaku Mashilo

- Rich Mnisi

- Zanele Muholi

- Oluseye

Ayotunde Ojo

Jody Paulsen

Usha Seejarim

Katlego Tlabela

Pierre Vermeulen

Luyanda Zindela

- Dominique Zinkpè

Works

Patrick Bongoy

Desert Flower, 2023Recycled rubber inner tube, metal parts on board

81.1 x 98.4 x 8.6 in. | 206 x 250 x 22 cm

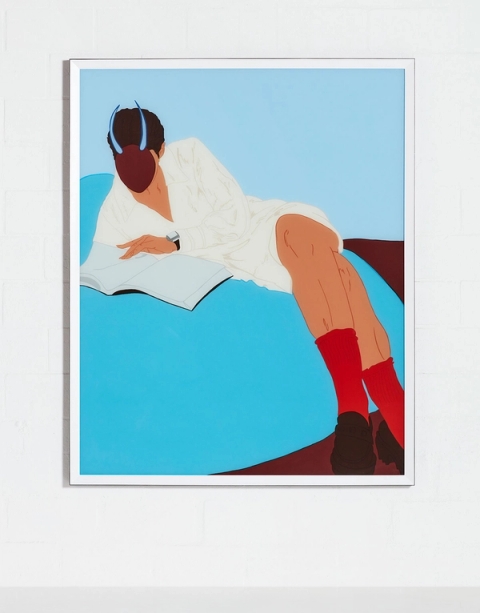

Manyaku Mashilo

You and your Soul are never not One, 2023Acrylic, ink, red ochre on canvas

78.75 x 55.13 in. | 200 x 140 cm

Chuma Maweni

Imbizo Dining Table II, 2023Kiaat, glazed stoneware

29.88 x 94.5 x 43.25 in. | 76 x 240 x 110 cm

Chuma Maweni

Imbizo Ibanjiwe I (A Gathering is Held), 2023Glazed stoneware

22.5 x 16.5 x 16.5 in. | 57 x 42 x 42 cm

Open edition

Justine Mahoney

Majesty, 2020Bronze, enamel

46.5 x 19.75 x 19.75 in. | 118 x 50 x 50 cm

Edition of 9, 2AP

Jesse Ede

Transit of Venus, 2023Bronze, granite

15.38 x 63 x 39.38 in. | 40 x 160 x 100 cm

Edition of 7, 2AP

Kamyar Bineshtarigh

Studio Wall V, 2023Wall paint, ink, cold glue on hessian backing

83.9 x 76 in. | 213 x 193 cm

Kamyar Bineshtarigh

Studio Wall VII, 2023Wall paint, ink, cold glue on hessian backing

81.9 x 62.3 in. | 208 x 158 cm

Sold

Madoda Fani

Khethiwe (The Chosen One), 2022Burnished, smoke-fired earthenware

40.13 x 25.25 x 25.25 in. | 102 x 64 x 64 cm

Sold

Andile Dyalvane

Nkcokocha (Mountain Peak), 2016Glazed earthenware, wenge

59 x 31.5 x 15.8 in. | 150 x 80 x 40 cm

Sold

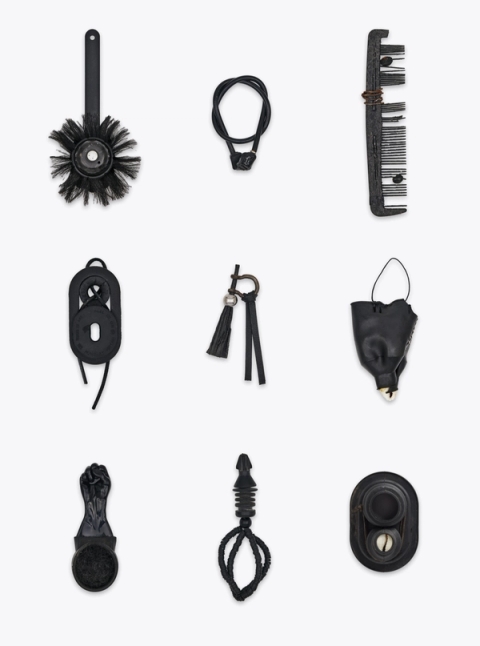

Oluseye

Eminado Series, Reunion 13, 2018 - OngoingFound objects, rubber, synthetic hair, cowry shells

28.38 x 28 x 3.75 in. | 72 x 71 x 9.5 cm

Zanele Muholi

Bonile III, The Decks, Cape Town, 2020Baryta print

Image and paper size: 23.5 x 18.6 in. | 60 x 47.4 cm

Edition of 8, 2AP

Zanele Muholi

Zimpaphe l, Parktown - Wallpaper, 2019Wallpaper

Variable: max. height 400 cm | 13.1 ft.

Edition of 2, 1AP

Porky Hefer

Piranha 1: Nerina, 2016Leather, sheepskin, steel

54 x 78 x 43.25 in. | 137 x 198 x 110 cm

Edition of 2, 1AP

Dominique Zinkpè

Poésie Humaine, 2021Bronze, enamel

78.8 x 19.8 x 18.5 in. | 200 x 50 x 47 cm

Edition of 5

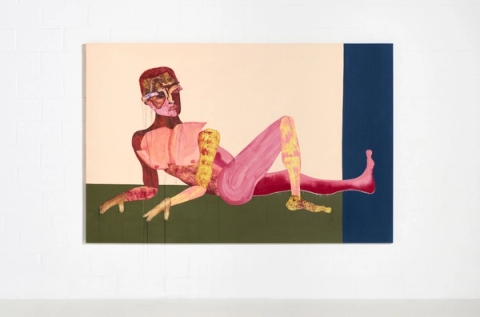

Jody Paulsen

Tomorrow Man, 2023Fabric, acrylic, ink and cotton thread on canvas

67.9 x 104.5 in. | 172.5 x 265.5 cm

Sold

!["The first time I felt at home in this city was when you let me add music to your playlist" / [Kim smiles] / Well... My playlist is called, At Home", 2021 Luyanda Zindela](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/33elzic6/production/b9044ef167de8eb3ddaec3e1845810a3f52554fb-1432x1825.jpg?auto=format&q=100&w=480)

Luyanda Zindela

"The first time I felt at home in this city was when you let me add music to your playlist" / [Kim smiles] / Well... My playlist is called, At Home", 2021Acrylic, marker on pine

94.5 x 71.25 in. | 240 x 181 cm

Pierre Vermeulen

Screamed the same scream cried the same tears, 2023Gold leaf imitate, sweat, acrylic, shellac on linen

78.8 x 70.9 in. | 200 x 180 cm

Sold

Tony Gum

Milk Bags, 2023Premium Satin Giclee Dibond mounted

59 x 39.4 in. | 150 x 100 cm

Edition of 10

Tony Gum

Cheese, 2023Premium Satin Giclee Dibond mounted

59 x 39.4 in. | 150 x 100 cm

Edition of 10

Kamyar Bineshtarigh

Studio Wall IX, 2023Wall paint, ink, graphite, spray paint, cold glue on hessian backing

81.1 x 198.4 in. | 206 x 504 cm