My Enquiry (0)

No artwork has been selected.

Please choose an artwork to enquire.

Enquiry Submitted

Thank you for your enquiry and interest in our artists’ work. A member of the gallery team will respond shortly.

000%

Isivivane (Cairn of Stones / Memorial): Pamella Dlungwana on Zanele Muholi's work

10 Jun 2024 (10 min) read

In this personal essay for Southern Guild’s Zanele Muholi monograph, Pamella Dlungwana recalls the community of care and activism the artist documented – and helped shape – through their pioneering photography of Black queer women.

Jikijela Ngamatshe (Casting Stones): Vee’s house - Johannesburg 2006.

Nestled in Jozi’s Berea, Vee’s place is an unassuming house with a granny flat that houses Kasha, Victor and Monique and later, Mo. Kasha and Victor are Ugandan queer rejects, exiled for flaunting their lesbian and trans identities. They have landed in Johannesburg through their interactions with FEW and Behind the Mask, both organisations housed at Constitution Hill and servicing the black queer community. Muholi is active in both, teaching photography skills to young journalists at Behind the Mask and running FEW with their then-partner, Donna Smith. Muholi is also getting ready for their first show at the Market Photo Workshop and much of what they have covered within the black lesbian queer community in Johannesburg will be on white walls.

The exhibition: Black and white images of some people I know, performing various mundane tasks or acts of affection. A wash basin has a naked woman; tall, big and seemingly unaware of the camera capturing her. She must know it’s there from the angle, must know she’s being viewed. I wonder what kind of relationship she has with the photographer to allow such an image to be taken.

I’m new to Jozi and this is my first time in an L-word loving, womyn-centred space. Black women surround me from morning to night. They are affectionate, jealous, suspicious and expressing their desire for each other, their sisterhood in open and honest ways. When I finally get close to Muholi, it’s through a conversation around gathering funds for an upcoming funeral.

‘We’ve lost one of our own.’

Someone my sister and everyone at the house knows has passed. Erased by a stranger’s hand for being openly lesbian and the family can’t do much about it. The womyn around me gather. Funds must be collected. Representatives must show up to support the family. Muholi is busy: Phone in hand, camera in the other. I’m moved by the organisation, the commitment to supporting this fallen comrade and Muholi’s insistence that this be documented. I want to know why the photograph. Why insist on that in such tragic circumstances? Am I being a fool or forgetful? I grew up to graveside poets and limited pics at the graveyard because most of the funerals I attended were under heavy surveillance. Some of the attendees would later be picked up to disappear for a while. No cameras allowed. Later, poets would give way to drum majorettes and pantsulas as 'After Tears' became a trend and photographers were welcome to capture the grand send-offs families organised for their loved ones. But the circumstances around this death somehow made the need for photography seem gauche to me.

“Without a record who will believe that all she had to be was a lesbian?”

This is Exhibit A. To successfully indict a government that is dragging its feet when it comes to ‘corrective rape’, one needs more than a protest, demands made to politicians. One needs an article that’s irrefutable and indelible by nature. After all, this is how some of our freedoms were won.

Wathinth’ Umfazi, Wathint’ imbokodo: Liesl’s flat - Vredehoek Cape Town 2010

The wall in front of me is plastered with miniature copies of my portrait. It’s a wallpaper of me and we’re here to play games and have a meal on a frigid Cape Town night. The people here are all friends but I’m still self-conscious. I want to disappear.

The games start and soon I forget. When we’ve had our fill of wine and laughs, it hits me that we haven’t spoken of any politics. There’s a new case involving someone most people in the room know but this evening we’ve taken the night off. Where some of us were gutted by the news, Muholi was in Khayelitsha, was at the clinic and sometimes, the break from the terrifying truth is all you can give yourself before running head-first into it again.

Coming back from a smoke break after most guests have left, I slip up. The topic comes up again. My friend crumples and I take my cue. Maybe Liesl will forgive me.

A pebble in your shoe: Gaborone Inn - Botswana 2014

Bandile and I are on a short break. We’ve been in Botswana on a self-funded residency to the Bessie Head/Seretse Khama museum in Serowe and have also come for a poetry festival. We meet Zanele and Liesl and are surprised to find them here. Neither is a poet. Muholi is here to meet Skipper, a Motswana activist working on trans-rights. “You’ve met Skipper, Pam, at FEW?” Zanele is jaunty, light and in high spirits. Camera always in hand, they are here to document the local movement. We have coffee between my sessions and Zanele informs me of the laws here, what Skipper and their crew have to work with. But Zanele is smiling in a way I’ve rarely seen. They’re confident things will work out and if not, Skipper and his ilk will wear out the system in time. They have the teeth for this fight.

A Rolling Stone: Motto By Hilton New York City, Chelsea - New York 2016

Terra and Lerato have collected me from my AirBnB close to NYU’s Galatin School of Individualised Study, our hosts for the conference we’re here to attend. Zanele is also here, invited in part to document and participate in the first black queer symposium held by the university. We’re now in the Meatpacking District where Zanele has been working since 5AM, emails and image selections and edits for the next show.

We’ve come too far to leave Zanele in the hotel on our only free day. When I get into the room, Muholi is in full production mode and I quietly start picking out items for them to wear. They are still in that terry cloth robe hotels believe signify luxury. If you run a bath, they will soak in it. My trick works and as they emerge from the tub, Terra and Lerato have packed the camera equipment away, leaving outside the one camera Muholi always has on them.

For the next few hours we’ll hit local Long Street, find haberdasheries and buy a cornucopia of what will become costume or accessories for Muholi’s self-portraits. We shop for ourselves, stop at and do the usual touristy things. The day is loaded with mirth, a notable absence of the heavy subjects we’ll be discussing once we’re mic’ed. Here, Terra, Lerato and I share Muholi, our friend who has one eye on the now and the other on the morrow. We help them shift focus from the politics and tuck into street food. We buy kitsch keepsakes and pose for a gallery of ridiculous street pics.

When we make it back to the hotel, Zanele starts blasting gospel music. They tell me that this is their current salve. The only balm that works for them these days. We all need a safe harbour, they tell me, and something shifts in Zanele as they sing along.

When we’re out, I ask the pair what travelling with Zanele is like. It’s good and quiet, they tell me. Copacetic until something breaks back home. “You don’t want to be around if something breaks,” they say. Lerato is sensitive and practical. Terra is more vocal yet emotionally reserved. In these two, Muholi chose their conspirators well. Fellow filmmakers and photographers, their ambition is to capture the immediate moments after the quake. The rumble.

I’ve had the fortune of being gifted the two portraits Zanele took of me in my home in Woodstock over a two-year period. I’ve been luckier still to have people send me these Faces and Phases snaps in the homes of collectors, on the walls of institutions. But when Zanele and I first discussed taking these portraits, having them adorn the houses of collectors was not the point. Zanele approached me because of my own work as a sex activist and vocal member of the queer community, how I used my words to reinsert pleasure and play into black lesbian/queer identities lest we be mistaken for ever-tortured sad sacks.

Before we sat together, we spoke at length about the importance of building a sustainable archive, an active record that charts where we are, where we’ve been, where we aim to land. I can be romantic and impractical but even I knew that a photo was not going to change the minds of miserable misogynists who wanted nothing but to tear me down. I knew though, that inserting myself into that sea of black-and-white images would spark international conversations around our plight at the time. But for a while the newspapers don’t report our trials, deaths, incarcerations. For weeks, the headlines scream about Soweto Pride, a bold one and an emphatic celebration in what was then, one the most dangerous places for any lesbian to be out.

Regardless, couples hold hands in public. We fight, love and propose love on national television. The cry that images of black women loving each other distract from ‘nation building’ projects has died along with some of the homophobic humans who spat them. I’d like to credit the series for these milestones but that would be too much. Faces & Phases as an active archive threw a rock, and then another, into isivivane and that grew. It takes a nation to shift such stagnant hateful beliefs, and we’ve all done our part.

The Zanele Muholi monograph is available for sale at both the Cape Town and Los Angeles galleries.

Click here to purchase and arrange delivery should you reside outside of either of these locations.

Pamella Dlungwana is a Durban-based writer with a passion for art-focused collaboration and articulation.

Images:

Zanele Muholi, ID Crisis, 2003

Zanele Muholi, Comfort, 2003

Zanele Muholi, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg, 2007

Zanele Muholi, Triple III, 2005

Zanele Muholi, Collen Mfazwe, August House, Johannesburg, 2012

Zanele Muholi, Bakhambile Skhosana, Natalspruit, 2010

Zanele Muholi, Pam Dlungwana, Vredehoek, Cape Town, 2011

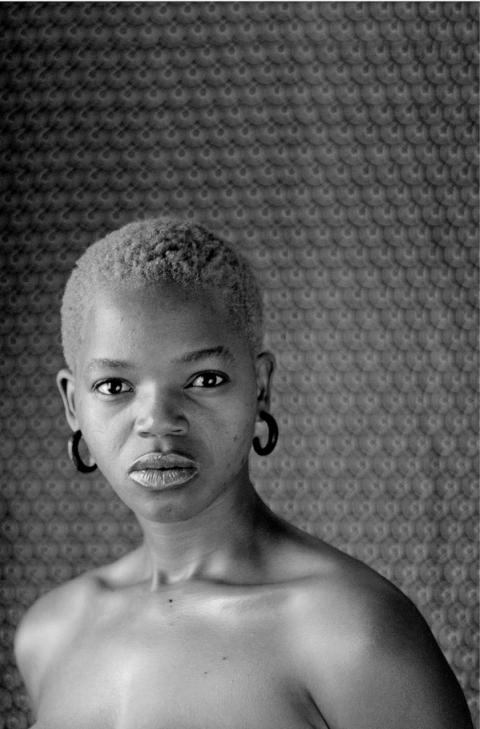

Zanele Muholi, Inno Tebogo Molaudzi, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2014

All images courtesy of the artist.